The 4th of March 2021 is a date I’ll never forget. I had a hospital appointment to discuss the results of tests on a lump in my left breast, just underneath the armpit.

My doctor asked me what I was expecting. I told him I thought it was probably a harmless cyst, to which he responded, simply, ‘No, it’s cancer.’

As he explained that I would need substantial surgery and radiation, and probably chemotherapy, I sat there speechless. One of the first things I said when I had regained my composure was: ‘I won’t be doing the Ironman this year, then?’

On paper, I’m about as low risk as you can get when it comes to cancer. I’m young (ish!), at 38, a normal weight and a lifelong non-smoker. I’ve always eaten a healthy, balanced diet and have no history of cancer in my family.

But one thing I had to learn to accept is that cancer does not discriminate. Though there are certain risk factors, it can happen to anyone, even fit and healthy triathletes – as much as we all like to think we’re invincible!

Check your breasts!

Women of all ages are advised to check their breasts regularly to get to know what feels normal for them. Coppafeel.org is a great website, packed with advice, resources and ideas of how you can get involved in raising awareness and fundraising.

Little guidance on training

Despite being bombarded with information in those first few weeks following diagnosis, there appeared to be very little guidance readily available for athletes who wanted to keep training during and after treatment.

Don’t get me wrong, cancer is hard on the body and mind, and there’s absolutely no shame in wanting to take it easy. But that just wasn’t me.

I’ve been a competitive swimmer since I was eight years old. But later in life, after becoming bored of the pool, I started to swim in open water and that naturally led me to marathon swimming, and then to multisport.

My first event was the London Triathlon. In a pattern that would be repeated in every race over the next decade, I came out of the water first, dropped a few places on the bike and was overtaken by literally everyone on the run.

After a few years of participating in Olympic-distance events, I completed my first 70.3 in Staffordshire in 2019. The full Ironman in Vichy was due to be my next race, but COVID-19 put an end to that plan, so I entered Ironman Cascais in 2021.

When I was diagnosed in March, I felt like I might never achieve my dream. Surely, it wasn’t possible for someone to undergo cancer treatment and finish an Ironman, right?

Slowly regaining mobility

The first stage in treating breast cancer like mine is usually surgery to remove the tumour. In my case, the cancer was locally advanced (Stage 3), meaning that it’d spread to several lymph nodes in my armpit.

As a result, I had to have them all removed – a procedure known as axillary lymph node clearance. The surgeon also had to remove a lot of tissue surrounding the tumour, to achieve something the doctors call ‘clear margins’.

When I came out of surgery, I couldn’t move my arm more than a few centimetres and had something called axillary web syndrome (or ‘cording’), which is essentially scarring of the connective tissues in the arm.

The hospital gave me exercises to do every day. Those first few weeks were very frustrating, but slowly I regained some mobility.

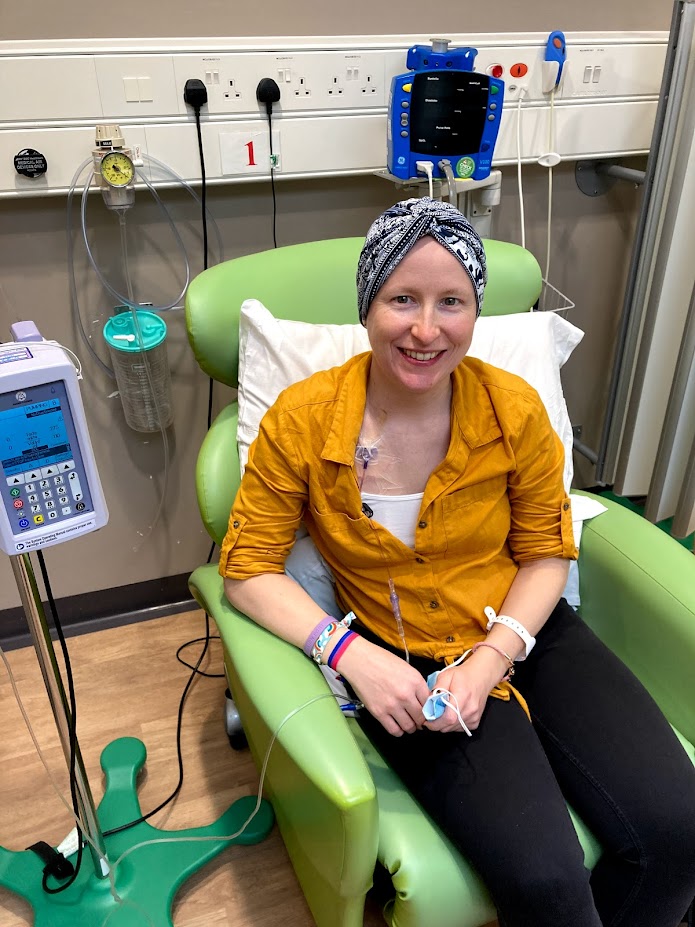

After surgery I had six rounds of chemotherapy, with infusions taking place every three weeks. These were initially injected directly into my ‘good’ arm, which caused some of the veins to collapse.

I eventually had a portacath fitted in my chest, which was a godsend! This meant that the drugs could be injected straight into the vein above my heart, avoiding further damage to my arm.

Coping with the side effects

People tend to think of chemotherapy and its side effects as being a horrific experience, and for some people it is. But some people don’t have any side effects at all. I was somewhere in the middle.

I suffered some of the common reactions – nausea, fatigue, hair loss, sore mouth and musculoskeletal pain – but was very lucky that they were well-controlled by medication (I had to take 22 pills on some days).

Thankfully, rather than losing my appetite it increased – my family joked that not even having cancer treatment could put me off my food! All the eating really helped with energy levels, though it did mean I put on weight.

One of the drugs, Epirubicin, also turned my urine bright pink!

Naïvely, I thought I’d be able to keep up a reasonable tri training regime during chemo or at least do enough of the three disciplines to maintain a reasonable level of fitness. But it wasn’t that simple.

Chemotherapy destroys a lot of your ‘good cells’ along with the bad ones, including the white blood cells which fight infection.

As my treatment was taking place during the pandemic, I couldn’t go anywhere where there were other people, ruling out the gym and pool. I couldn’t swim in open water either.

I ran a few times but was unable to reach any kind of distance without becoming exhausted, and I found it difficult to properly hydrate. Cycling was really the only realistic option for me.

As my arm was still weak, I didn’t think it was safe to take Flora (my two-wheeled pride and joy) out on the roads, so I ended up spending a lot of time sat on my turbo trainer – thank goodness for Zwift!

I also did a lot of walking. Keeping active helped me cope with the fatigue and manage my weight, but also helped with the stress and anxiety that naturally comes with a cancer diagnosis.

Patience is key

At the time of writing, I’m still having radiotherapy, but it’s been several weeks since I finished chemo and I’ve been able to slowly resume training (radiotherapy isn’t a walk in the park, but it’s much less hard on the body than chemo).

For the most part, it feels like re-training after an injury – I’ve lost a lot of fitness and muscle strength, so I’m having to build distance and intensity up very slowly. But there are also extra things to think about now.

As my left arm no longer has a functioning lymphatic system, there’s a risk that fluid could build up in the tissues, causing an incurable condition called lymphoedema.

I therefore try to avoid anything that might lead to swelling or infection of the arm, such as rigorous exercise in hot weather or cuts and grazes that could become infected.

Chemotherapy and radiation can damage the heart and lungs, so I must be careful not to do too much too soon and put strain on any vital organs. I just have to be more patient and more careful – not my strong points!

Finishing active treatment won’t be the end of the road for me. For the next 10 years, I need to take a hormone medication called tamoxifen.

My cancer is oestrogen receptor positive (often shortened to ER+), which means that oestrogen helps the cancer cells to grow and divide. Tamoxifen works by blocking the oestrogen from connecting to the cancer cells, which reduces the risk of the cancer coming back.

Unfortunately, tamoxifen has its own side effects associated with the forced onset of early menopause – hot flushes, nausea, fatigue and dry skin – none of which are particularly helpful if you’re trying to train in endurance sport!

Relish the training

Despite the long-term side effects of the chemotherapy and radiation treatment, the biggest change is not a physical one. It’s a cliché, but cancer puts everything into perspective.

All of a sudden, life is too short to be doing things that you don’t enjoy. For me, I’ve become more positive, and better able to cope when training gets tough.

I used to have a love-hate relationship with running, always seeing it as the hardest part of training (and racing). It wasn’t until I couldn’t do it anymore that I suddenly realised what a privilege it was.

Now, when it’s pouring with rain and my legs feel like concrete, I don’t wish I was inside nursing a cup of tea. I relish it!

I haven’t given up on the Ironman. I’m now enrolled into Cascais 2022, giving me just under a year to prepare. I know it will be a challenge, but as time goes on I’m starting to believe that it’s possible.

Now, when I cross that finish line, it will feel like even more of an achievement. But my goals are no longer solely race-oriented.

I want to try and add to the rapidly growing movement to raise awareness of breast cancer in younger women and share what I’ve learned with other triathletes diagnosed with breast cancer.

Most of all, I want to show people that although cancer is a life-threatening diagnosis, it doesn’t have to mean the end of living. With patience and the right advice, you can get back to what you were doing before, and maybe even enjoy it more!

Post-cancer training advice

Mel Young has been personal training for over 20 years and is the owner and founder of Amazon24 Fitness. During this time, she’s helped many women return to fitness post-cancer treatment.

Below are a few simple steps to help post-cancer patients get back to some kind of training regime. Please remember that specific training should only be undertaken once cleared by the consultant. Every woman will be different depending on the severity of their cancer, treatment and result of recovery.

- Create a plan with low-intensity workouts through the week ensuring rest and recovery sessions are planned. Track these sessions with a diary of how your body felt and whether sessions felt easy or hard. By doing this, you may see a pattern of when you felt at your strongest and weakest, so you can set sessions at various intensities through the week, slowly loading sessions to see fitness progress. Get yourself a good coach to help you with this if you aren’t sure.

- Set small achievable targets each week for all training sessions and be open minded to adapt them if needed. This will encourage consistency, which in turn encourages progress. Create a chart to see how far you’re progressing.

- Use RPE – Rate of Perceived Exertion – within your workouts to help set levels of intensity and stick to them. This can be through HR training or sets and reps in strength work.

- Listen to your body. If you feel tired, rest. Don’t get stressed if you miss a training session. Fuel well, sleep, recover and rise again the next day to tackle your training.

- Look out for signs of trauma around the infected area, especially if you’ve had surgery. Bruising, red marks or soreness are signs that your body isn’t happy. Listen, react by getting it checked and lower training intensity or stop for a few days until all is clear.

- If you suffer with edema (the swelling of the arm after lymph nodes have been removed), then you may be advised to wear a tight support bandage to alleviate swelling. You should find that exercise will help this and keep swelling down. Make it a priority to keep your shoulder joints healthy by introducing mobility, stability and strength exercises into your programming.

Top image: Getty Images